Data Analysis

Questions to David Rotermund

By Jan Wiersig, modified by Udo Ernst and translated into English by Daniel Harnack.

Three aspects of data analysis shall be covered in this chapter: spectral analysis via the Fourier transformation, generation of random numbers and working with probability distributions, and the elementary methods to fit models to measured data.

Fourier Analysis and Filter Operations

The Fourier analysis is the most important integral transformation in physics. It not only allows to find the frequency content of a temporally varying signal, it also comes in handy to simplify the calculation of convolutions and thus applying filters efficiently to data. In every programming language, thus also in Matlab, the Fourier transformation is implemented as the so called ‘Fast Fourier Transform’ (FFT) to optimize calculation time and to spare the user the effort to program it themselves.

Fourier Transformation

It has to be distinguished between the discrete Fourier transformation and the continuous Fourier integral. First, we will define the Fourier integral and then introduce the discrete version. Although the computer, due to the discretization of any function

Fourier Integral

The Fourier integral can be defined as follows:

Attention: in the literature sometimes a pre-factor of

\(x(t) = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} \hat{x}(\omega) \exp\left( i\omega t \right) \, d\omega\) .

| If |

x(t) | dt \, < \, \infty$ . |

The Fourier transformation of a function is a representation of that function as a superposition of harmonic oscillations with angular frequency

Here,

If

\(\hat{x}_k = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} x(t) \exp\left( -ikt \right) dt\) . (9.1)

The reverse transformation is written as an infinite sum:

\(x(t) = \sum_{k=-\infty}^{+\infty} \hat{x}(t) \exp\left( ikt \right)\) .

By rescaling of the t-axis by

For further properties of the Fourier transformation you may consult the instructive Wikipedia article.

Discrete Fourier Transformation

In the computer, functions are defined on discrete sampling points in a finite interval. Let us assume a function

\(\hat{x}_k = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} x(t') \exp\left( -ikt' \right) \, dt' \approx {\frac{1}{2\pi}} \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} a_n \exp\left( -ik 2\pi t_n/T \right) \Delta t'\) .

Here,

\(\hat{x}_k \approx A_k = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} a_n \exp\left( -i 2\pi nk/N \right)\) . (9.2)

This equation describes the discrete Fourier transformation, the implementation of which we will discuss more extensively in the following paragraph. The corresponding reverse transformation is:

\(a_n = \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} A_k \exp\left( i 2\pi nk/N \right)\) .

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)

The discrete Fourier transformation is invoked in Matlab by the command a_trans = fft(a);, where

Calling help fft shows that the Matlab-implementation of the FFT does unfortunately not divide the result by the number of sampling points, which is the number of element of a vector a. This has to be done ‘manually’.

The performance gain of the FFT in comparison to a non-optimized, brute force algorithm is impressive: the execution time of the FFT is already faster by 4 orders of magnitude(!) for

n_power = 12;

t = zeros([n_power 2]);

for power=1:n_power

fprintf('N=2^%i...\n', power);

n = 2^power;

a = rand([n 1]);

%%% Calculates FFT of signal 'a'

tic;

a_fast = fft(a);

t(power, 1) = toc;

%%% Calculate Fourier transform by 'brute force'

tic;

a_slow = zeros([n 1]);

a_slow(1) = sum(a);

exp_k1 = exp(-complex(0, 1)*2*pi*(0:(n-1))'/n);

exp_k = 1;

for k=1:n-1

exp_k = exp_k.*exp_k1;

a_slow(k+1) = sum(a.*exp_k);

end

t(power, 2) = toc;

end

%%% Plot execution times and the

%%% acceleration factor

figure(1);

subplot(2, 1, 1);

plot(1:n_power, t);

legend({'FFT' 'Fourier brute force'});

xlabel('power of two'); ylabel('t [s]');

subplot(2, 1, 2);

plot(1:n_power, t(:, 2)./t(:, 1));

xlabel('power of two'); ylabel('factor');

Application: The Power Spectrum#

This paragraph deals with the question of how the FFT is applied to a signal

n = 100; dt = 0.01; f = 5;

a_sine = 42*sin((0:(n-1))*dt*2*pi*f);

a_step = (0:(n-1)) >= n/2;

The signals are sampled with a frequency of

fft_a_sine = 1/n*fft(a_sine);

fft_a_step = 1/n*fft(a_step);

Now we want to investigate how much energy is contained in the different frequency bands. For this we calculate the so called power spectrum

- In the first place we have to make sure, how Matlab stores the calculated coefficients

- Which frequency does the coefficient

- Let us now look at the coefficients

If we want to know the amplitude of the oscillation with frequency

phi_5Hz = (abs(fft_a_sine(1+5))+abs(fft_a_sine(n-5)))

The output 1.7640e+03 is indeed the square of the amplitude 42.

| A signal with |

A_k | = | A_{-k} | $ holds). A corresponding Matlab command plots the power spectrum for a step function, which has, as expected, a broad band spectrum: |

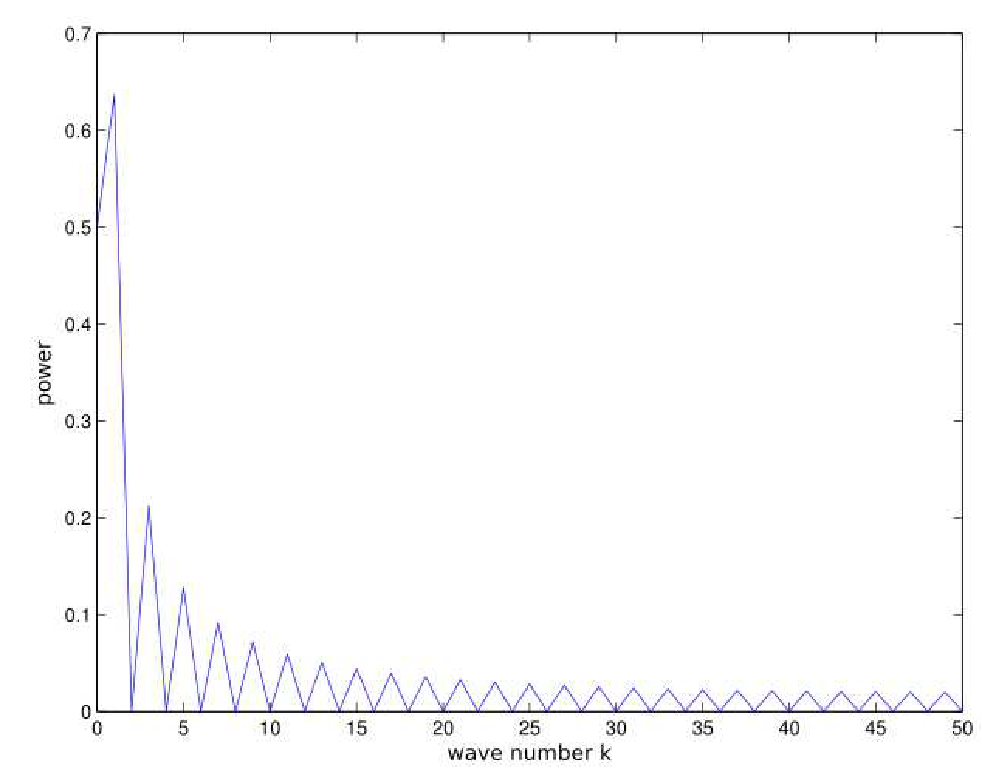

plot(0:(n/2), [fft_a_step(1) 2*abs(fft_a_step(2:(n/2)+1))]);

xlabel('wave number k');

ylabel('power');

Figure 9.1.: Power spectrum of a step function.

The Convolution Theorem

The fast Fourier transform is not only useful to determine the frequency content of temporal signals, but also to perform so called ‘convolutions’. A convolution of two functions

\(h(t) = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f(t') g(t-t') \, dt'\) (9.3)

Here,

Applications of this equation are numerous in physics, and reach from simple filter operations to timely resolved frequency analysis (examples will be discussed later). First, we want to understand the connection between convolutions and the Fourier transformation. As a short notation of the application of the Fourier transform

Now we apply the Fourier transform to both the left and the right side of the Definition (9.3) and gain after short computation,

or, in short notation,

\(h = F^{-1}\left[ 2\pi F[f] \cdot F[g] \right]\) (9.4)

The advantage of equation (9.4) over (9.3) lies in the computation speed of FFT: despite a three-fold transformation, calculating equation (9.4) is faster than computing the integral in (9.3), since the convolution integral corresponds to an element-wise multiplication of the Fourier coefficients in the Fourier space

Non-periodic Functions

The discrete Fourier transformation can be applied to any arbitrary function

Still, the FFT can be used with non-periodic functions, provided the convolution kernel

Application: Filtering of a Time Series

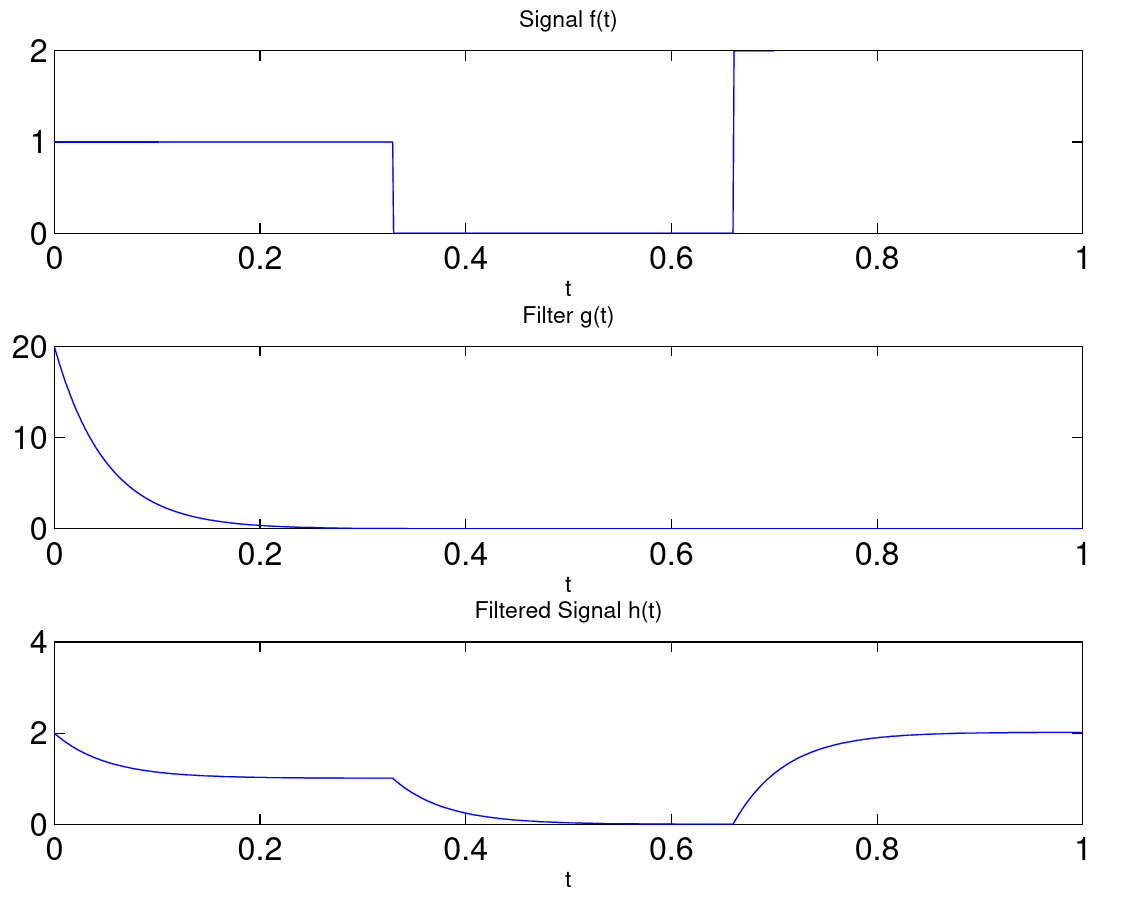

Let us consider the filtering of a temporal signal as an example for the application of the convolution theorem. The signal is chosen to be a rectangle function, that is 1 in the first third of the data acquisition period, then jumps to 0 and increases to 2 in the last third. The filter shall be an exponentially decaying function

% parameter

n = 1000;

t = (0:(n-1))/n;

tau = 0.05;

% rectangle signal

f_signal = (t < 0.33)+2*(t > 0.66);

g_filter = 1/tau*exp(-t/tau);

f_filtered = real(ifft(1/n*fft(f_signal).*fft(g_filter)));

% plot

figure(1);

subplot(3, 1, 1);

plot(t, f_signal); xlabel('t'); title('Signal f(t)');

subplot(3, 1, 2);

plot(t, g_filter); xlabel('t'); title('Filter g(t)');

subplot(3, 1, 3);

plot(t, f_filtered); xlabel('t'); title('Filtered Signal h(t)');

Figure 9.2.: Low pass filtering

Figure 9.2.: Low pass filtering

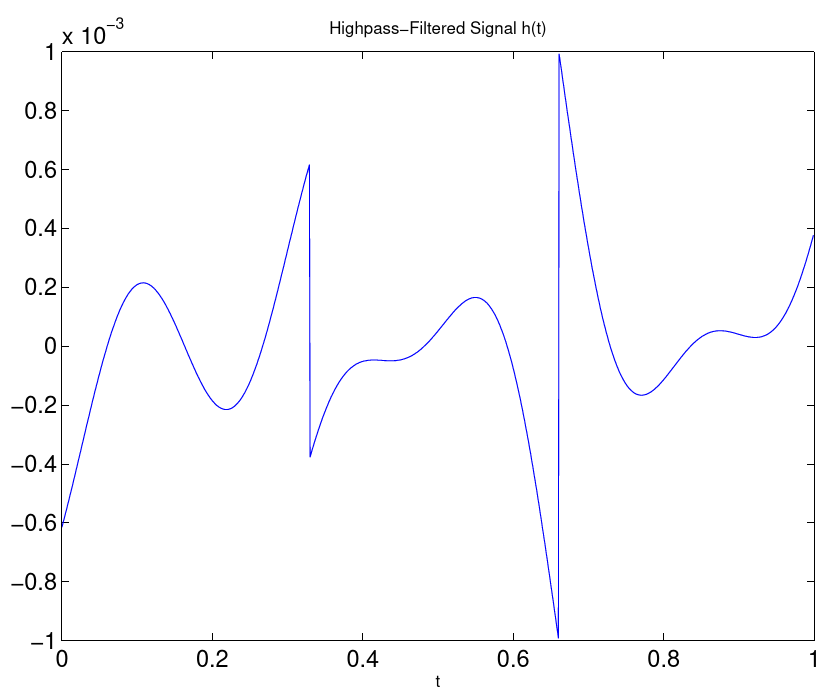

Equation 9.4 reveals a further, interesting possibility to apply filter operations: The term

% construct high pass filter

k_min = 5;

g_filter_highpass = zeros([1 n]);

g_filter_highpass(1+k_min:end-(k_min-1)) = 1;

f_filtered_highpass = real(ifft(1/n*fft(f_signal).*g_filter_highpass));

% plot

figure(2);

plot(t, f_filtered_highpass); xlabel('t');

title('Highpass-Filtered Signal h(t)');

Figure 9.3.: high pass filtering

Figure 9.3.: high pass filtering

When defining own filters in frequency space, one has to be cautious: most of these filter are acausal and change the phase of

To conclude, two technical remarks shall be made. First, the FFT is also defined for higher dimensional functions. The Matlab-commands are (i)fft2, (i)fft3 and (i)fftn. This is useful for example to filter digital images. Second, the FFT can be applied to a specific dimension fft(a, [ ], n), where the empty brackets indicate that a ‘zero-padding’, as described earlier, shall not be made. This form of the FFT is worth considering, when several functions, that are stored in the columns or rows of a matrix, shall be transformed in one go.

Application: Examples for Convolution Operations

To end this section, some further examples for the application of the convolution theorem in physics and data analysis shall be mentioned:

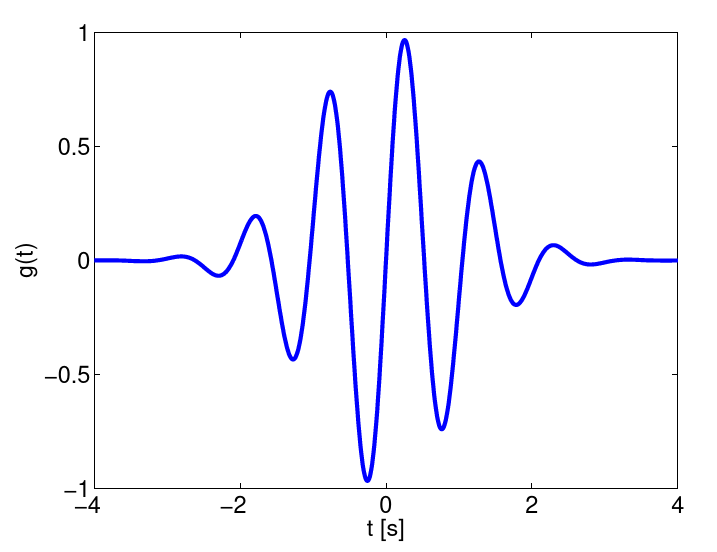

Wavelet Transformations.

Fourier transformations are ill suited for signals, whose spectrum changes over time. This also includes signals which do contain periodic oscillations, but where the frequency is subject to fluctuations. In wavelet transformations, a signals is convoluted with a filter

Figure 9.4.: Wavelet filter

A spectrum is obtained that not only depends on the frequency, but also from time. A much used wavelet is the Morlet-wavelet, which is a harmonic oscillation multiplied with a Gaussian curve.

Correlation Functions.

The cross correlation

\(C(\tau) = \int f(t) g(t+\tau) dt\) (9.5)

Here,

Equation (9.5) is not directly a convolution, this means one has to be careful when applying the convolution theorem. Utilizing that $Ff(-t) = \hat{f}(-k)$ it holds:

The following examples come from the theoretical neurophysics:

Reverse Correlation.

A simple model for the response properties of neurons in the visual system assumes that the response

Again,

When the stimulus

After application of the convolution theorem, we get:

Recurrent Networks.

Neuronal networks usually have a one- or two-dimensional topology, where a neuron at position

If the weight are invariant to translation via

Probabilities and Distribution Functions

Distributions

Often the problem arises to estimate an underlying distribution

It thus holds

Matlab provide the function histc, that calculates distributions from samples. The syntax is:

h = histc(x_samples, x_min:Delta_x:x_max{, dim});

The vector h contains the number of samples that lie in the intervals determined by the second argument (the intervals do not have to be equidistant!).

Histograms can also be calculated from multi-dimensional distributions of

Random Numbers

Creating random numbers is a often required function of a programming language. There are numerous algorithms to create numbers that are distributed ‘as random as possible’, these will however not be covered here. Instead we will concern ourselves with creating random numbers from arbitrary given distributions.

Uniformly Distributed Random Numbers

For uniformly distributed random numbers, Matlab provides the command rand. It creates random numbers in the interval

a = rand;

b = rand([n 1]);

c = rand(n);

d = rand(size(array));

The first command gives exactly one random number, the second one a vector of

It might be a good idea to generate the same sequence of random numbers when restarting a program. In this way, faulty code can be tested more effectively or different numerical procedures can be compared with the same realization of a random process. To accomplish this in Matlab, the ‘seed’, i.e. the starting value of an internal random number generator, can be set to a fixed value by

rand('state', start_value);

Normally Distributed Random Numbers

Normally distributed random numbers are created by the command randn. The syntax is analogue to rand. The distribution has the mean

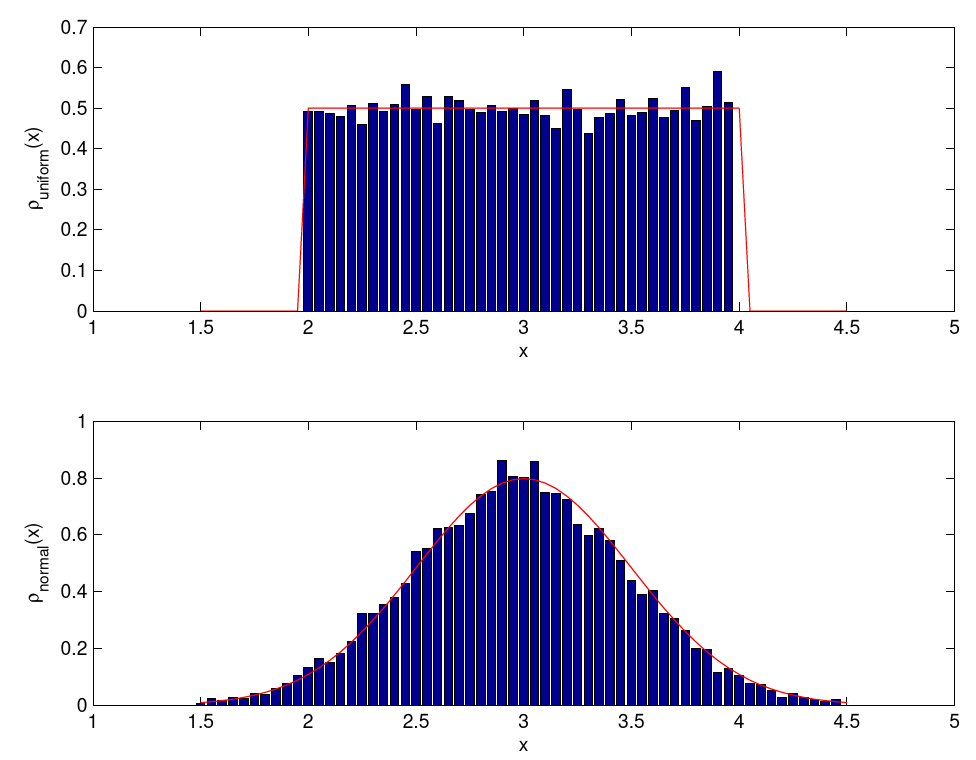

To generate other uniform or normal distributions, it is best to scale and move the numbers generated by rand and randn. The following Matlab code for example draws samples from a uniform distribution in the interval

%%% number of samples

n_samples = 12345;

%%% draw random numbers and rescale

x_uniform = 2+2*rand([n_samples 1]);

x_normal = 3+0.5*randn([n_samples 1]);

%%% estimate distributions

x_axis = 1.5:0.05:4.5;

rho_uniform = histc(x_uniform, x_axis)/n_samples/0.05;

rho_normal = histc(x_normal, x_axis)/n_samples/0.05;

%%% plot exact and estimated distriutions

figure(1);

subplot(2, 1, 1);

bar(x_axis, rho_uniform);

hold on;

plot(x_axis, (x_axis >= 2).*(x_axis <= 4)/2, 'r-');

hold off;

xlabel('x'); ylabel('\rho_{uniform}(x)');

subplot(2, 1, 2);

bar(x_axis, rho_normal);

hold on;

plot(x_axis, 1/sqrt(2*pi)/0.5*exp(-0.5*(x_axis-3).^2/0.5^2), 'r-');

hold off;

xlabel('x'); ylabel('\rho_{normal}(x)');

Figure 9.5.: Uniform and normal distribution.

Random Numbers from Arbitrary Distributions

To generate random numbers from arbitrary distributions

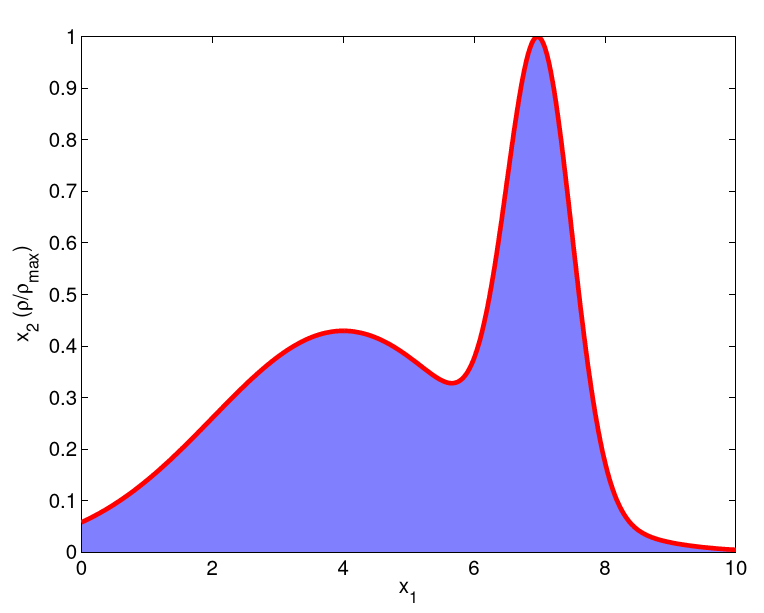

The Hit-and-Miss Method.

Let

Figure 9.6.: Hit-and-miss method: draw two uniformly distributed random numbers

The hit-and-miss method can be very time consuming. It is easier if the inverse function of the primitive

\(y = F(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x \rho(x') \, dx'\) ,

and thus

Interval Nesting.

The primitive

Tabulation.

If many random number have to be drawn, the inverse function

\(x = y_2 (F^{-1}(y_{j+1})-F^{-1}(y_j)) + F^{-1}(y_j)\) .

Regression Analysis

Analysis of measured data is an important part in evaluating physical theories and models. Usually, some parameters of the physical models have to be fitted to the data and then the adapted model shall be scrutinized whether it describes the data well. The mandatory techniques of parameter fitting as well as the evaluation of the goodness of a fit will be discussed in the following.

General Theory

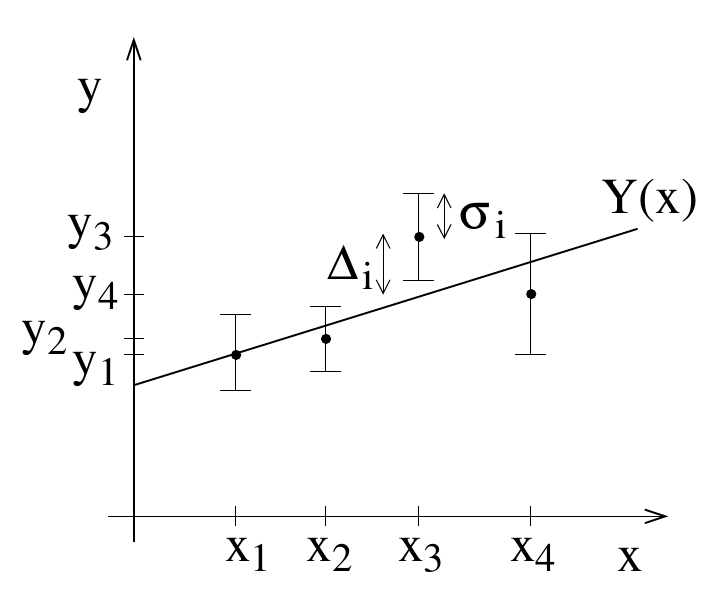

Let us assume that data is provided as pairs of values

to a data set.

Figure 9.7.: Fitting a curve to data points.

It is the aim to adjust the values of these parameters such that the function

\(\Delta_i = Y(x_i;a_1,\ldots,a_M)-y_i\) .

We choose our fitting criterion such that the sum of the squares of the deviations becomes minimal. This means that we have to tune our parameter values

is minimized. This method is dubbed least squares method. It is not the only possible method, but the one that is most commonly used.

Usually the data points have an estimated error bar (the confidence interval), that we denote as

\(\chi^2(a_1,\ldots,a_M) = \sum_{i=1}^N\left(\frac{\Delta_i}{\sigma_i}\right)^2 = \sum_{i=1}^N\frac{[Y(x_i;a_1,\ldots,a_M)-y_i]^2}{\sigma_i^2}\) .

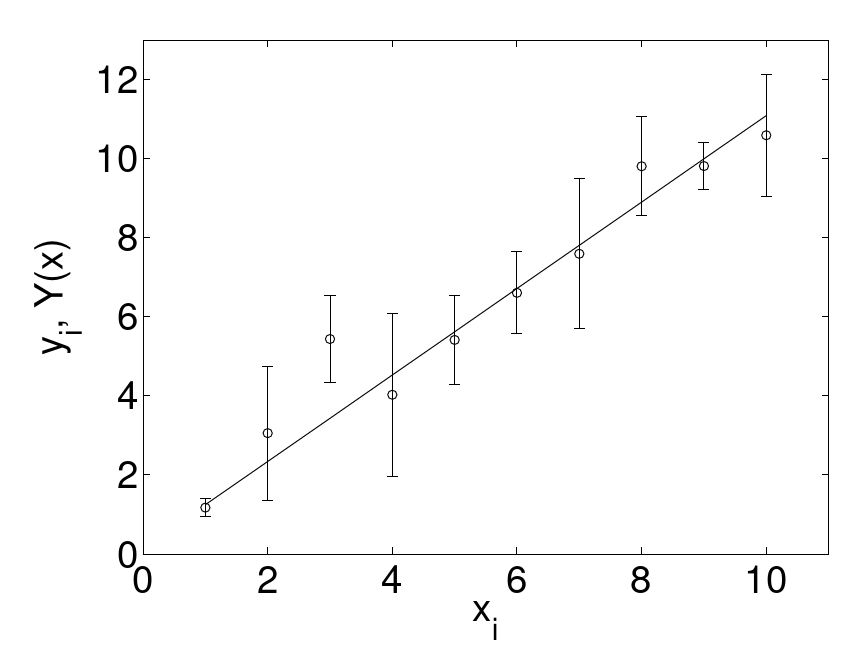

Linear Regression

We now want to fit a straight line to the data points,

\(Y(x;a_1,a_2) = a_1+a_2 x\) .

This type of fitting is called linear regression. The two parameters

becomes minimal. The minimum can be found by taking the derivation of the equation and setting it to zero

We now introduce the following quantities

These sums are calculated directly from the data points, are thus known constants. Hence we can rewrite the previous system of equations as

This is a system of linear equations with two unknowns

\(a_1 = \frac{\Sigma_y\Sigma_{x^2}- \Sigma_x\Sigma_{xy}}{\Sigma\Sigma_{x^2}-(\Sigma_x)^2}, \quad a_2 = \frac{\Sigma\Sigma_{xy}-\Sigma_y\Sigma_{x}}{\Sigma\Sigma_{x^2}-(\Sigma_x)^2}\) (9.6)

In a second step we want to estimate the error bars for the parameters

Insertion of the equations (9.6) yields

\(\sigma_{a_1} = \sqrt{\frac{\Sigma_{x^2}}{\Sigma\Sigma_{x^2}-(\Sigma_x)^2}} , \quad \sigma_{a_2} = \sqrt{\frac{\Sigma}{\Sigma\Sigma_{x^2}-(\Sigma_x)^2}}\) .

As an example we consider:

Here the fit parameters are

Figure 9.8.: An example of linear regression. A straight line

Goodness of the Fit

It is clear that the fit is locally good, if the deviation of the function is smaller or approximately equal to the error bar. We consider the upper boundary

Insertion into the definition of

\(\chi^2(a_1,\ldots,a_M) = \sum_{i=1}^N\left(\frac{\Delta_i}{\sigma_i}\right)^2 = \sum_{i=1}^N\frac{[Y(x_i;a_1,\ldots,a_M)-y_i]^2}{\sigma_i^2}\) .

yields

\(\chi^2 \approx N-M\) .

As an example we again refer to fig. 9.8. Here,

Non-linear Regression

In many cases, the fitting of a non-linear function can be broken down through a clever variable transformation to the fitting of a linear function. As the first example, the commonly occurring case

shall be observed. One thinks for example of exponential decays. With the variable transformation

we get the linear function

\(Y(x;a_1,a_2) = a_1+a_2 x\).

A second example are power laws of the type

\(Z(t;\alpha,\beta) = \alpha t^\beta\) .

the variable transformation

also gives a linear function.

The source code is Open Source and can be found on GitHub.