Differential Equations

Questions to David Rotermund

By Jan Wiersig, modified by Udo Ernst and translated into English by Daniel Harnack. David Rotermund replaced the Matlab code with Python code.

Ordinary Differential Equations

In many fields of science, problems occur where one or several quantities vary dependent on time, e.g. oscillations or decay processes. The description of these processes can be formalized by differential equations. As a simple example, radioactive decay may serve. An amount of radioactive material is give at time

with decay constant

The solution of a differential equation is not a number, but a function. Here, the solution is

with place

Alternatively to the previous notation, the differential equation can also be interpreted as an ordinary system of differential equations of 1. order with double the number of variables

Using the ‘phase space variable’

Here, the first three components of

Euler Method

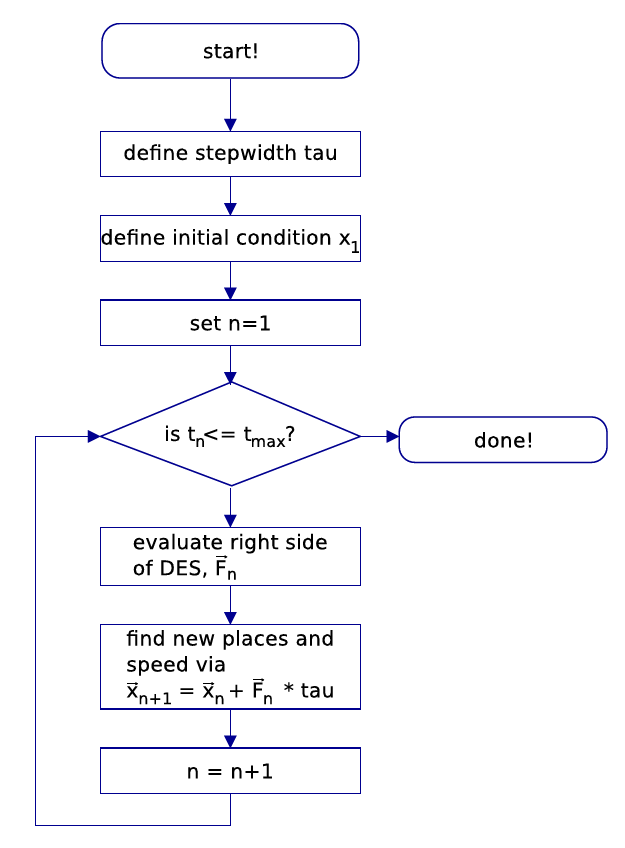

Figure 8.1.: Flow plan for the Euler integration scheme. The aim is to find the solution of the initial value problem of the differential equation system (DES)

numerically. For this, we first replace the differential quotient by the right sided derivation

respectively

The truncation error is of 2. order in the step width

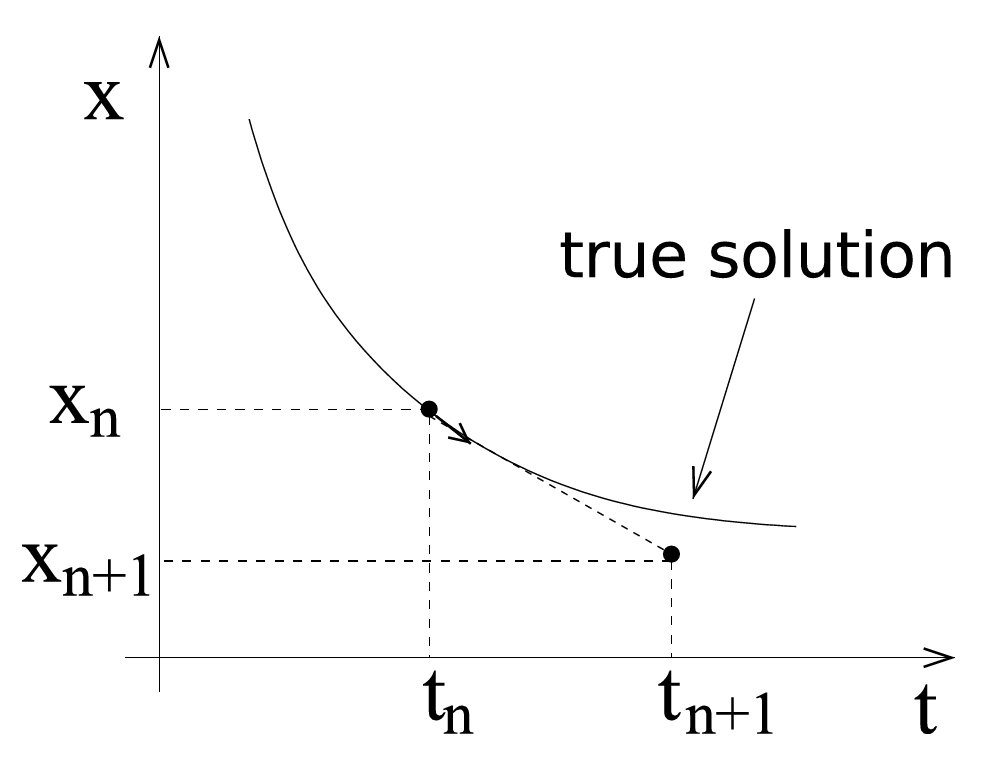

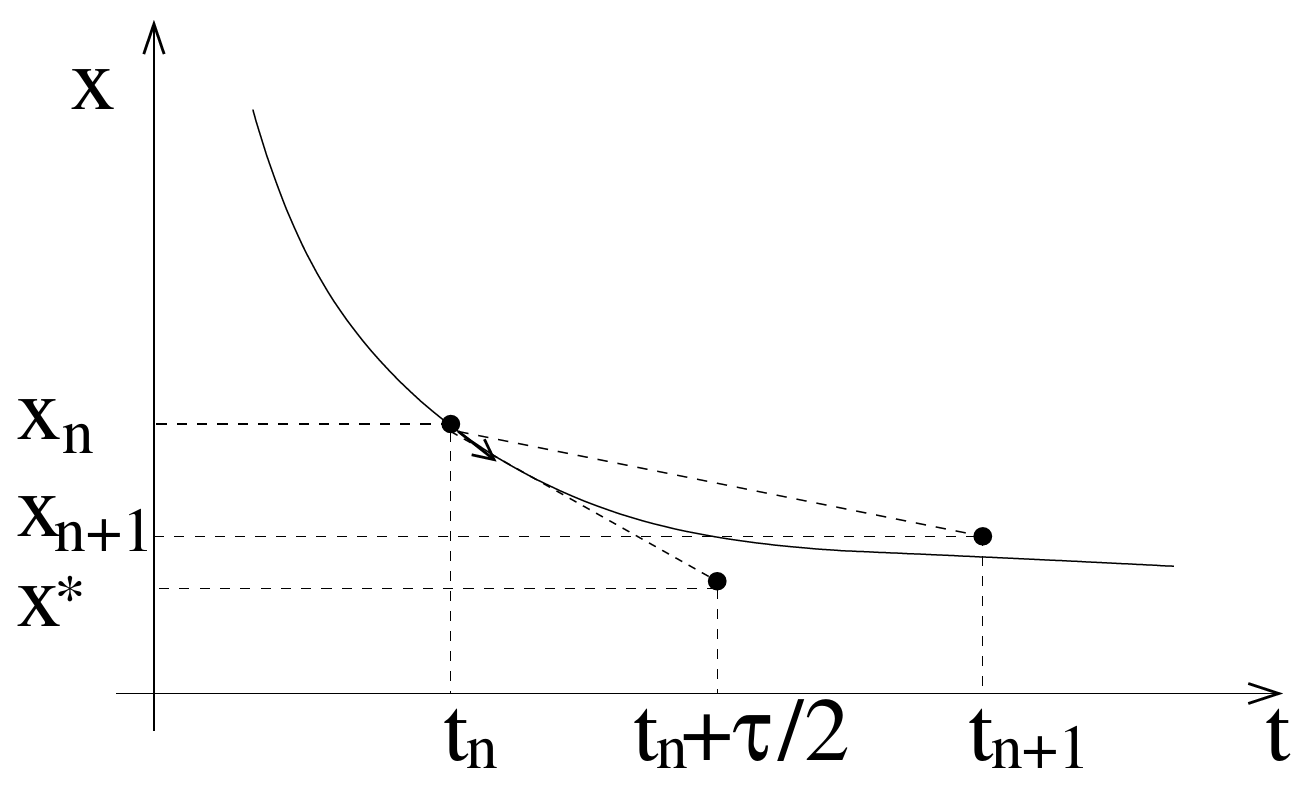

This method is illustrated in figure 8.2.

Figure 8.2.: This figure shows a comparison between the true solution (continuous line) and a numerical solution found by the Euler method in one time step (dotted).

Schematically, the algorithm is as follows:

- Choose a step width

- Specify an initial condition

- Set the counter

- While

- Evaluate the right side of the DES

- Find the new places and velocities via

- Increase the counter by 1

- Evaluate the right side of the DES

The result is a trajectory

The local error is characterized as the truncation error per time step. It is of order

The global error of the method of Euler is thus of order

Example: The Planar Pendulum

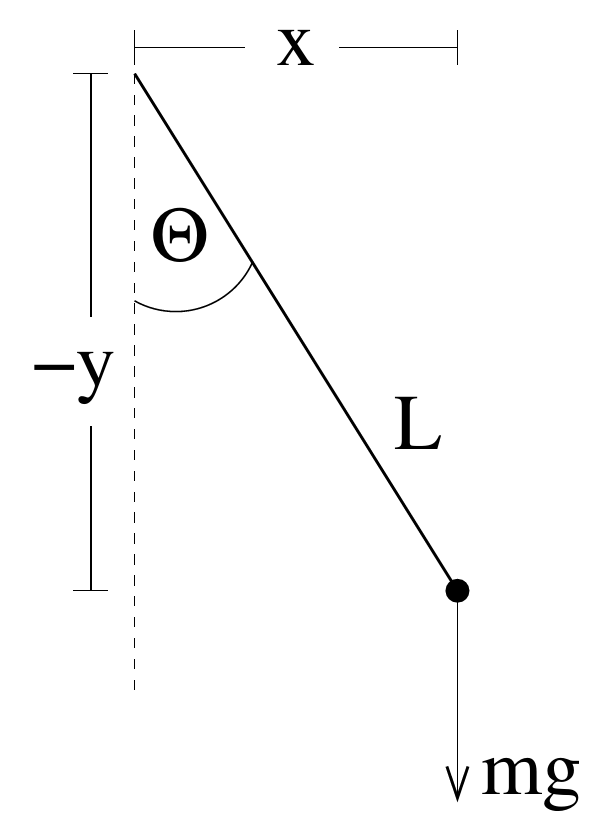

Figure 8.3.: Schematic depiction of a planar pendulum.

As an example we will discuss the planar pendulum. The pendulum consists of a point-shaped mass

with gravitational acceleration

Taking the time derivation while considering

This yields

Insertion into the energy equation finally yields

This is the energy of the pendulum, expressed by the angle of deflection

This gives the equation of motion for the planar pendulum

In the approximation of small deflections, the problem can be solved analytically. With

We thus choose the ansatz

with amplitude

The known result is, that in the approximation of small deflections, the period of oscillation is independent of the deflection.

The general case of arbitrarily big deflections is not as easy to handle. We will solve this problem numerically. The analysis above shows, that it is sensible to choose

The important point is,

The equation of motion can thus be written with the scaled time as

This equation of motion is free from both units and parameters! Introducing the natural unit thus not only prevents range errors, but also simplifies the problem.

With the generalized speed

The following is a program that solves the equations of motion numerically via the method of Euler.

For the sake of clarity, the program is divided into functions.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import typing

def derive_pendulum(t: float, s: np.ndarray):

return np.array([s[1], -np.sin(s[0])])

def euler_integration(t: float, x: np.ndarray, tau: float, derivs: typing.Callable):

return x + tau * derivs(t, x)

# set initial conditions and constants

try:

theta0: float = float(input("initial angle = "))

except ValueError:

theta0 = 90

print(f"theta0 = {theta0}°")

x: np.ndarray = np.array([theta0 * np.pi / 180, 0])

try:

tmax: float = float(input("time = "))

except ValueError:

tmax = 100

print(f"tmax = {tmax}")

try:

tau: float = float(input("step width = "))

except ValueError:

tau = 0.001

print(f"tau = {tau}")

time: np.ndarray = np.linspace(

start=0,

stop=tmax,

num=int(np.ceil(tmax / tau)),

endpoint=True,

)

t_plot = np.zeros_like(time)

th_plot = np.zeros_like(time)

for i, t in enumerate(time):

# remember angle and time

t_plot[i] = t

th_plot[i] = x[0] * 180 / np.pi

x = euler_integration(t, x, tau, derive_pendulum)

# figure

plt.plot(t_plot, th_plot)

plt.xlabel("time")

plt.ylabel("theta")

plt.show()

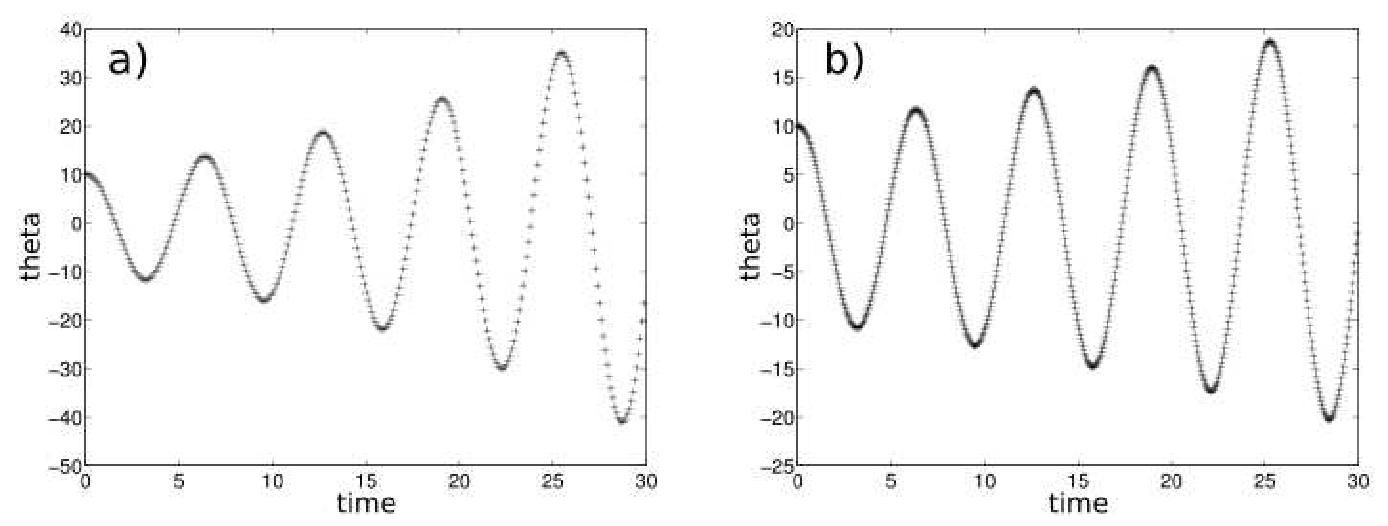

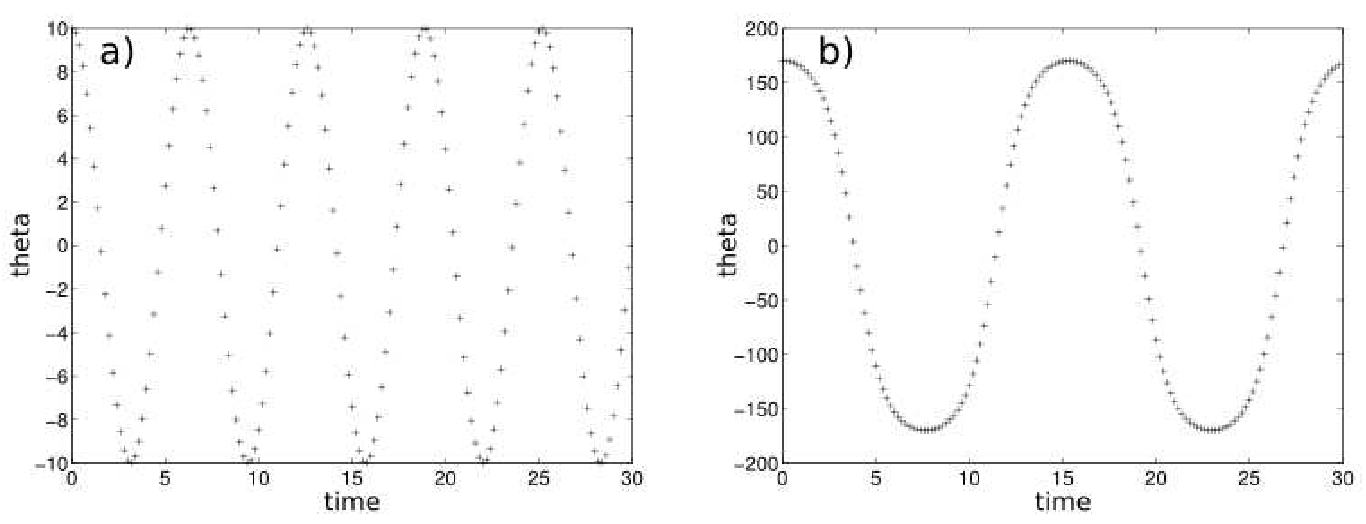

Fig. 8.4(a) shows a solution of the equation of motion by the method of Euler with step width

Figure 8.4.: Numerical solution of the pendulum dynamics following the method of Euler. The initial angle is

Runge-Kutta Method

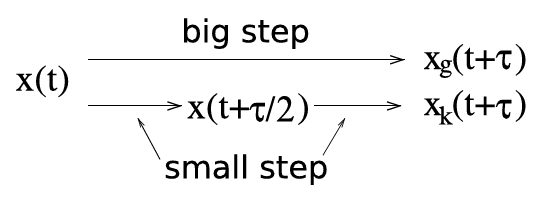

Now we will discuss a method that is superior to that of Euler, since the error term is of higher order. The idea is to find the changes in time (derivatives) of the variable at a sampling point that lies at the half of the interval, over which the integration step is supposed to run. The actual integration step is then performed with the derivative at this point, and is one order more precise than the Euler method, as we will show in the following.

We again consider the DES

In the following we will compare the Taylor series

with the method of Euler with half the step width

It can be seen that

This yields the Runge-Kutta method of 2. order

The truncation error is of 3. order in

Figure 8.5.: Scheme of the Runge-Kutta method, 2. order.

To better understand this method, we investigate a very simple differential equation

With the initial condition

Let us now consider a translation

Comparing this with the result obtained by the method of Euler

shows that the method of Euler gives the exact solution up to the first order. Now we look at the Runge-Kutta method of 2. order, which is

Inserting the lower equation in the upper one yields

Thus we see that the Runge-Kutta method of 2. order represents the exact solution up to the 2. order.

Runge-Kutta Method of 4. Order

In complete analogy, the Runge-Kutta method of 4. order can be derived. We will thus skip this procedure and directly look at the result:

The truncation error is of 5. order in the step width

Inserting and rearranging yields

We can see that the Runge-Kutta method of 4. order is the exact solution up to the 4. order of the series. We thus assume that this method needs far less time steps than the method of Euler. Fig. 8.6(a) confirms this. The result for the planar pendulum with a small deflection angle of

Figure 8.6.: Numerical solution of the dynamics of the planar pendulum via Runge-Kutta, 4. order. the step width is

Adaptive Methods

Thinking about the previously introduced methods, two questions arise:

- Given a DES, how should the step width

- Can the step width

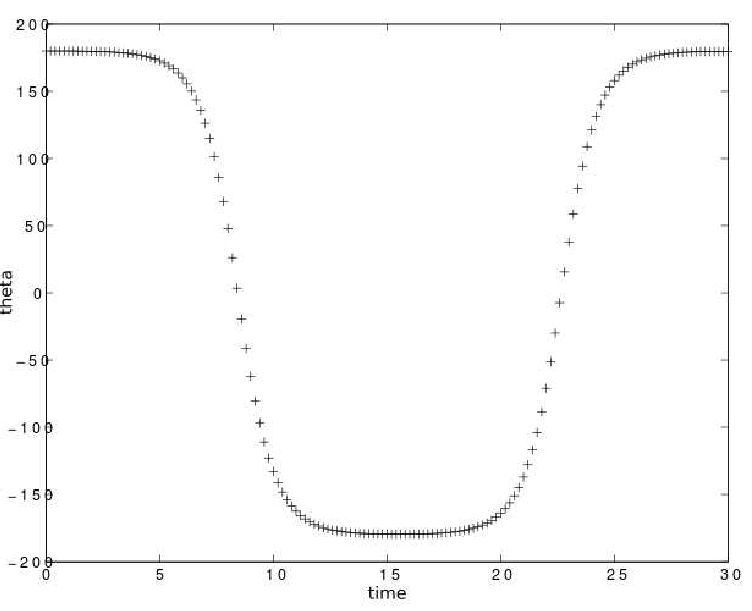

Figure 8.7.: Runge-Kutta method of 4. order: pendulum with initial angle =

Both questions lead toward the so called adaptive methods, where the step width

With these two approximations, a relative error

with the machine precision

Here,

| if |

||

| if |

||

| if |

Feasible values are

Python Solver

import numpy as np

import scipy

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def derive_pendulum(t, s):

return [s[1], -np.sin(s[0])]

# set initial conditions and constants

try:

theta0: float = float(input("initial angle = "))

except ValueError:

theta0 = 90

print(f"theta0 = {theta0}°")

x: np.ndarray = np.array([theta0 * np.pi / 180, 0])

tmin: float = 0.0

try:

tmax: float = float(input("time = "))

except ValueError:

tmax = 100

print(f"tmax = {tmax}")

try:

tau: float = float(input("step width = "))

except ValueError:

tau = 0.1

print(f"tau = {tau}")

time: np.ndarray = np.linspace(

start=tmin,

stop=tmax,

num=int(np.ceil((tmax - tmin) / tau)),

endpoint=True,

)

t_eval = np.linspace(tmin, tmax, 1000)

sol = scipy.integrate.solve_ivp(

fun=derive_pendulum, t_span=[tmin, tmax], y0=x, t_eval=time, method="RK45"

)

plt.plot(sol.t, sol.y[0] / np.pi * 180)

plt.xlabel("time")

plt.ylabel("theta")

plt.show()

scipy.integrate.solve_ivp(fun, t_span, y0, method='RK45', t_eval=None, dense_output=False, events=None, vectorized=False, args=None, **options)

Solve an initial value problem for a system of ODEs.

This function numerically integrates a system of ordinary differential equations given an initial value:

Here t is a 1-D independent variable (time), y(t) is an N-D vector-valued function (state), and an N-D vector-valued function f(t, y) determines the differential equations. The goal is to find y(t) approximately satisfying the differential equations, given an initial value y(t0)=y0.

Some of the solvers support integration in the complex domain, but note that for stiff ODE solvers, the right-hand side must be complex-differentiable (satisfy Cauchy-Riemann equations). To solve a problem in the complex domain, pass y0 with a complex data type. Another option always available is to rewrite your problem for real and imaginary parts separately.

method:

| ‘RK45’ (default) | Explicit Runge-Kutta method of order 5(4). The error is controlled assuming accuracy of the fourth-order method, but steps are taken using the fifth-order accurate formula (local extrapolation is done). A quartic interpolation polynomial is used for the dense output. Can be applied in the complex domain. |

| ‘RK23’ | Explicit Runge-Kutta method of order 3(2). The error is controlled assuming accuracy of the second-order method, but steps are taken using the third-order accurate formula (local extrapolation is done). A cubic Hermite polynomial is used for the dense output. Can be applied in the complex domain. |

| ‘DOP853’ | Explicit Runge-Kutta method of order 8. Python implementation of the “DOP853” algorithm originally written in Fortran. A 7-th order interpolation polynomial accurate to 7-th order is used for the dense output. Can be applied in the complex domain. |

| ‘Radau’ | Implicit Runge-Kutta method of the Radau IIA family of order 5. The error is controlled with a third-order accurate embedded formula. A cubic polynomial which satisfies the collocation conditions is used for the dense output. |

| ‘BDF’ | Implicit multi-step variable-order (1 to 5) method based on a backward differentiation formula for the derivative approximation. A quasi-constant step scheme is used and accuracy is enhanced using the NDF modification. Can be applied in the complex domain. |

| ‘LSODA’ | Adams/BDF method with automatic stiffness detection and switching. This is a wrapper of the Fortran solver from ODEPACK. |

The source code is Open Source and can be found on GitHub.